Alfred McCoy: The British Empire and Scientific Racism

Justifying Western abuse in the 19th century — Part Four of a series on McCoy's 'To Govern the Globe'

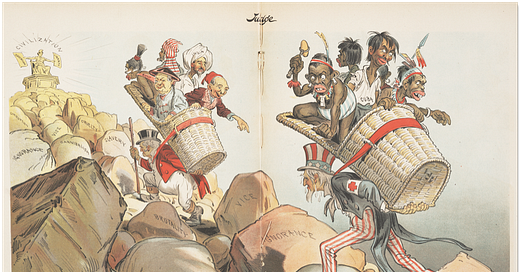

Just as Christianity legitimated slavery during the Iberian age, so a distortion of evolutionary science formed the ideological framework for the British imperial era, creating a racial hierarchy to excuse both the cruelty of European conquest and the harshness of its colonial rule in Africa and Asia.

—Alfred McCoy, To Govern the Globe

Take up the White man's burden

—Rudyard Kipling, “White Man’s Burden” (1899)

This is the fourth in a series that looks at Alfred McCoy’s To Govern the Globe, a magisterial account of the history of what I would call the “Western imperial project,” the successful attempt, starting in the mid-1400s, to control the non-Western world, its people and wealth.

All parts of this series are found at the top of the main page under the Book Club pull-down menu. They are, to date:

Introduction: To Govern the Globe

A look at the plan of the book and the concept of governing “ages”Alfred McCoy: The Quest for Global Control

Discusses the Iberian Age, the world order of Portugal and Spain, and the role of religion in the subjugation of peoplesAlfred McCoy: A World in Transition and the Rise of Capital Rule

The Dutch encroachment on Spanish and Portuguese rule, and the rise of the first corporations

Today we look at the transition from Dutch to British control and the period of the next great age, that of the British Empire.

A Brief Note

As usual with posts like these, this is a paid-subscriber posts for the reason outlined here.

From Dutch to British Dominion

Chapter 3 of the book details the transition, at the end of the Iberian Age, first to Dutch, then to British dominion. The transition phase includes the rise of capitalism — the title of the chapter, in fact, is “Empires of Commerce and Capital.” The cruelty also continued. (All emphasis below is my own.)

Indeed, the Iberian vision of expansive sovereignty—acquisition of terrain by conquest and oceans by exploration—would continue under Dutch and British hegemony, illustrating the capacity of these global systems to survive the empires that created them. As the Dutch extended their colonial rule across Java and the British across India in the eighteenth century, the violence of their transgressions against the sovereignty of indigenous states would approach anything the Iberians had done in Africa or the Americas. Thanks to the British and Dutch decisions to strip their colonial subjects of civil liberties and carry the transatlantic slave trade to new heights, the Iberian hierarchy of human inequality would, in all its cruelty and tragedy, continue.

The success of the early East India companies (Dutch and British) pointed the way to an evolving economic system, one where joint-stock companies were a de facto “company (or surrogate) state”. In other words, these early corporations were handed state power.

For much of the seventeenth century and well into the eighteenth, the driving force in European colonization would be a myriad of joint-stock companies—notably, the Virginia, Massachusetts Bay, Dutch West India, French East India, Hudson’s Bay, Royal African, and many more.

In the process, Europe’s empires were evolving away from the quasi-feudal Iberian system toward a more capitalist, market-based commerce. In the metropoles of Amsterdam, London, and Paris, monarchs and legislatures devolved a portion of their state power to those chartered companies, which were the world’s first real corporations, with balance sheets, shareholders, elected directors, and legal personae. During the seventeenth century as well, the British East India Company (EIC), like its Dutch counterpart, became a de facto “company state” with delegated royal authority to build forts, make laws, sign treaties, coin money, and make arrests. Out on the imperial periphery, such chartered companies served as the fulcrum for contact between Europe’s monarchies and indigenous states, whether Indian maharajahs, Arab emirs, or African chiefs. Thus, they slowly knit European commercial enclaves into territorial empires that would, in the course of the eighteenth century, extend to cover the whole of India and Indonesia.

Thus evolved a hybrid, transitional form of commerce that “fused state coercion and commercial monopoly to secure hyper-profits.”

Of course, slaves were involved:

These chartered companies employed a hybrid form of commerce called mercantilism that fused state coercion and commercial monopoly to secure hyper-profits. While the Dutch advocated free trade and open seas in principle, their VOC [the Dutch East India Company] was ruthless in crushing any competition for the spices of Southeast Asia. To control the export of nutmeg and mace, it curtailed unregulated production in the Banda Islands of eastern Indonesia by slaughtering their populations or deporting them to serve as slaves elsewhere.

As was extensive commerce in drugs:

In pursuit of mercantilist profits, European empires active in Asia during the eighteenth century found the trade in addictive substances—coffee, tea, tobacco, and opium—enticingly susceptible to lucrative monopolies. Given the light weight and high value of these drugs, and the certainty that customers habituated to caffeine, nicotine, and morphine would always return, companies were assured of both recurring sales and soaring profits. After discovering the exceptional gains to be made from the India–China opium trade, the VOC headquartered at Jakarta, Indonesia, increased its imports of Indian opium from just 617 kilograms in 1660 to 87 metric tons by 1699, retaining some for local sales and sending the rest to China, where addiction would grow rapidly.

But the full transition to the next great age doesn't occur until the justification of Western enslavement changes — which tells you (again) how much the rise of the West depended on the debasement of non-Western people, their thingification (treatment as inhuman objects), and the constant violation of their sovereignty.