Alfred McCoy: The Quest for Global Control

The Iberian Age — Part Two of a series on McCoy's 'To Govern the Globe'

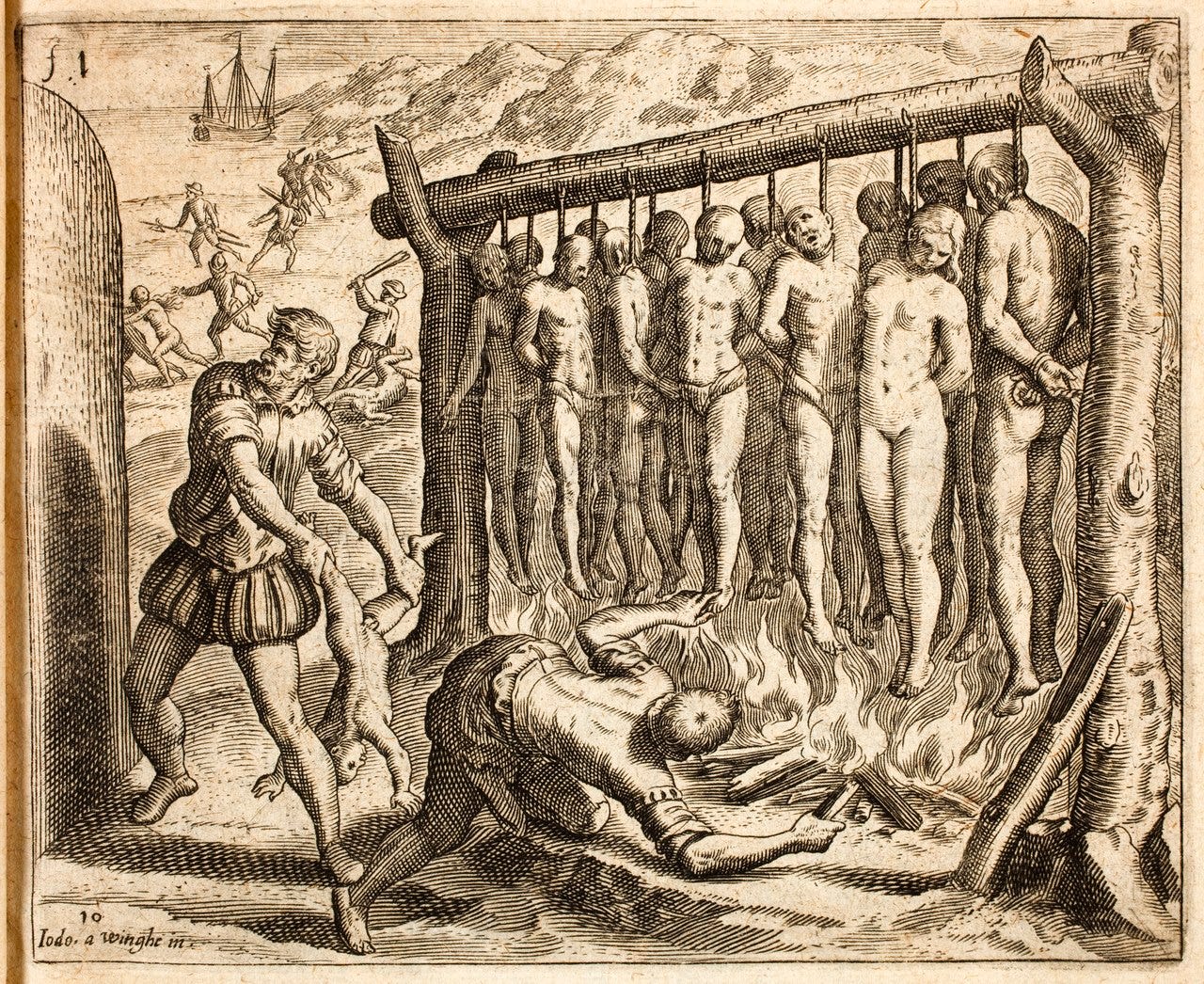

For the next ten years, those conquistadors swept the island of Hispaniola, enslaving the population and slaughtering any who resisted. In the process, they reduced the original population of 400,000 to just 60,000.

—Alfred McCoy, To Govern the Globe

I recently started a short series that looks at Alfred McCoy’s To Govern the Globe: World Orders and Catastrophic Changes.

In it he covers all the truly global empires, starting with Portugal and Spain, under the rubric of “world orders.” Note that empires are less enduring than orders, since orders include the rules by which truly global empires draw legitimacy and are allowed. The “Iberian order” encompassed several empires, each ruled under the same “permission structure” (my phrasing), delivered, in this case, by the Pope himself.

The introduction to the series is here…

and it starts like this:

As we enter the next phase of the imperial Western experiment … as we wait for announcements that will firm up our understanding of the pivot our President takes … as we watch dismantled what should never, perhaps, have been built, it’s useful to take a long view of what we’ve done, how long we’ve done it, and how America’s turn as king of the place was thought out and managed. Until it wasn’t — wasn’t thought out; wasn’t very well managed.

If you haven’t figured it out, “we” in the statement above is us in the West.

This is the second of what I anticipate to be four in the series — the introduction (linked above); this piece, on the Iberian order; another on the Dutch and English colonization; and the last closer to home, on our own attempt at a universal domain. I may add a fifth, since McCoy closes with climate change, which he rightly believes will disrupt the entire project, just (so he thinks) as China has taken the reins.

A Note on These ‘Book Club’ Reflections

First, all of these pieces are found under the ‘Book Club’ pulldown at the top of this site main page.

Second, this and the pieces like it are paid-subscriber posts, for the reason outlined here.

Third, I quite enjoy writing these diversions, and have many more planned. As I mentioned earlier, there’s quite a lot to learn from Bill Clinton and James Patterson’s novel, The President Is Missing. Clinton reveals a lot. As well, though I haven’t read it, the same may be true of Hillary Clinton’s tome about the struggles of a fictional, put-upon female Secretary of State.

And beyond question I’ll return to the book that started these reflections, David Graeber and David Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything, which traces humanity’s “conquest and empire culture” to neolithic days. Why this culture and not another? Did we have to end up this way? Graeber says no.

To Govern the Globe: The So-Called ‘Age of Discovery’

McCoy opens his examination of the Iberian Age (named after the Iberian peninsula, Portugal and Spain) like this:

[From Chapter 2: The Iberian Age]

In August 1960 on Lisbon’s historic waterfront, Portugal staged an elaborate commemoration for a minor prince known as Henry the Navigator, who died in 1460. Led by the president of Brazil, a delegation of international dignitaries inaugurated the spectacular Monument to the Discoveries, which soars above the Tagus River to a breathtaking peak of 171 feet. At the apex of this massive concrete structure stands Prince Henry, larger than life, holding up a model sailing ship and pointing across the Atlantic toward “the roads of the sea.”Some two hundred miles south at the Sagres Peninsula, naval vessels from fourteen nations sailed in parade formation past the ruins of the prince’s castle. Overhead thundered jet fighters from Britain, Spain, and the United States, paying tribute to the famous Sagres Academy, where Henry reputedly gathered the world’s most brilliant cartographers and mathematicians to map those roads to exploration. After the jets’ roar had faded and the ships had sailed away, more than three hundred historians attended an international conference in Lisbon to reflect on the remarkable role of that scholar prince in launching the Age of Discovery.

But there was another date in the prince’s biography that was of great historical consequence, yet little discussed during those days of celebration—1441, the year that marks the start of the modern struggle over human rights. That was the year one of Prince Henry’s voyages of discovery reached a point on the African coast eight hundred miles south of Lisbon that the ship’s crew would mistakenly name Rio Douro (river of gold). Instead of the gold they were searching for, however, they found an unexpected prize: twelve captive slaves, whom they likely seized from a Tuareg desert encampment. When they returned to Lisbon, docking just a few miles downriver from where that soaring monument now stands, the prince’s response was not what one would have expected from such a celebrated figure.

“I see before my eyes,” wrote the royal chronicler of Henry’s reaction, “how great his joy must have been … not for the number of those captives, but the hope, oh Sainted Prince!, for others you could have in the future.” Indeed, three years later, more of his ships returned, holds filled to capacity with 235 slaves seized in raids further down the African coast. When they docked, crowds gathered as Prince Henry, astride a strong horse, claimed his rightful share of the human cargo, the “royal fifth” of 46 slaves. The rest were divided into lots that separated families, with much weeping, says the court chronicler, as “mothers clung to their children and were whipped with little pity.”2 Nonetheless, that chronicler celebrated the enslavement of those Africans who once “only knew how to live in a bestial sloth,” but now “turned themselves with a good will into the path of the true faith.”

On the other side of the Atlantic in October 1982, the presidents of Mexico and the Dominican Republic inaugurated a monument with a more somber message. Rising one hundred feet above the waterfront of Santo Domingo, a statue of the friar Antonio de Montesinos, gazing out across the Caribbean Sea, raises a giant bronze hand in an angry gesture to commemorate the impassioned sermon he gave here in 1511, denouncing Spanish abuse of the Amerindians. Flanked by the uniformed military of both nations, the president of Mexico pointed out that this had been “the first time a voice was raised in defense of human rights. Never before in the history of humanity had the victor questioned the basis of his victory.” Indeed, that sermon marked the start of the Iberian world’s long, painful appraisal of the dark underside of Prince Henry’s legacy.

In 1502, as the first ships carrying Spanish colonists and conquistadors to the New World approached Santo Domingo, their commander had told them: “You have arrived at a good moment…. There is to be a war against the Indians and we will be able to take many slaves.” For the next ten years, those conquistadors swept the island of Hispaniola, enslaving the population and slaughtering any who resisted. In the process, they reduced the original population of 400,000 to just 60,000 [emphasis mine].

Thus begins the story of Western global conquest of non-Western lands. The abrogation of rights of all non-Western people is fully half of the story, from start to end. Every step in the Western expanse is a tale of abuse, brutality, and mass murder.

Slaves Forever

As we’ll see in each of these ages, the abuse of non-Western people is the necessary bride to Western global expansion. And in each of these ages, that cruel abuse acquired a permission structure. In the case of the Iberian Age, permission to murder and dehumanize native people came from the pope. In addition, the post-medieval energy equation continued that dynamic.