“Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.”

—John F. Kennedy

“The state and early civilizations were often seen as attractive magnets, drawing people in by virtue of their luxury, culture, and opportunities. In fact, the early states had to capture and hold much of their population by forms of bondage”

—James C. Scott, Against the Grain

I’ve been writing about how hunter-gatherer and early neolithic lifestyles are both different from the lives most in the West “enjoy” and also are viable alternatives to it. That is, there’s nothing inevitable about kingdoms and empires as a method of organizing society — it’s just what our European ancestors settled into, or were forced into by the ethnic group that overran their lands millennia ago.

For more on that, see here:

Many readers have since asked, “OK, we’re stuck with our rulers — so what do we do? If living controlled in hierarchies is simply a choice made by our ancestors, how do we get out of it now? What is the mechanism of change?”

Valid questions all. I think the answers start with the ideas below.

Three Roads Home

If we think of tribal, hunter-gatherer, or small village life as “home” — after all, as a species we spent almost 95% of our time adapted to smaller, low-hierarchy communities — what’s the machine that breaks these states, these giant engines of control, so we can free our lives?

Keep in mind, those of our species who pathologically love control, will not give it up easily, no more than an emperor would change place with a salt mine slave. Not a normal abnormal emperor at least, not Jamie Dimon, say, or Elon Gates.

This means that control will have to be torn from their grasp. How? I see three ways.

• Electoral decapitation and system restructuring, whereby those in control are removed from power by organized peaceful means and the system rebuilt to be much more fit for the purpose. A transition, in other words, of both leaders and systems from oppressive and predatory engines to egalitarian and nurturing ones.

I’m not sure this option is likely, but this is the “theory of change,” as it’s called, of most sincere, progressive, Party-aligned Democrats, voters and operatives alike. Sanders supporters in his two failed runs were driven by this idea — reform the system using the system’s rules.

• Forceful overthrow and system restructuring, whereby those in control are removed against their will using unapproved means and the system rebuilt. This is the “tell, don’t ask” approach. People in control are told or made to leave, and the place is remodeled when cleared of their debris.

As the Kennedy quote above makes clear, this method often occurs when the first method fails and people have reached their limit. When asking fails, eventually telling takes over, even if it takes a while, years or centuries. All empires fall; all king-controlled states break down; all corrupt big city machines eventually lose power. Often the reason for these failures is forceful revolt — overthrow outside of constitutional means.

But we can’t say this happens all the time. Yes, all empires fall, but not always from revolt. That brings up the third reason for things to change.

• Collapse, whereby a system fails on its own, brought down by its own inadequacy or felled by an external force. A drought will do kingdoms in. Disease does the same. A meteor shattered the rule of the dinosaurs, collapse on a global scale.

And needless to say, we’re on the verge of it now — collapse of an empire that’s arguably in its last throes, by which I mean the rule of the West over all of the rest of the globe; plus collapse of a climate system that sustains every species adapted to Holocene temperatures.

The Sumerian empire fell for a combination of reasons — population shift and drought being two of them. The Aztec empire was overthrown by Western expansion — the Spanish and Portuguese hunt for global colonies — but the Mayans fell much as the Sumerians did, through drought and social exhaustion. A Greek Dark Age ended the Mycenaeans — the world of Agamemnon and Achilles — just as a Roman Dark Age ended, well, Rome.

Can Collapse Be a Good Thing?

And here’s the rub: we think of collapse as a tragedy. It’s almost built into the name. A “lapse” is a fall from something, often religion (“lapsed Catholic”), and “co-lapse” first meant a group that falls together.

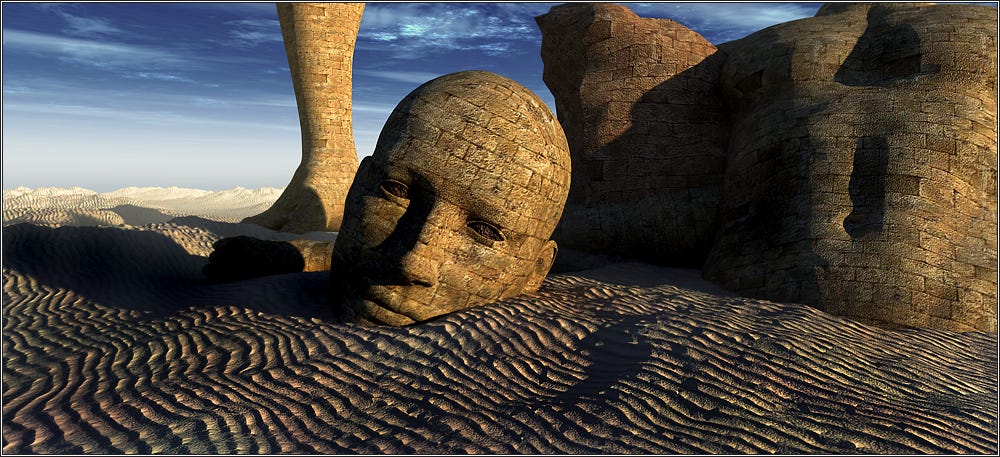

“Falling” is never thought good, and we often think of temples and monuments, ruined and abandoned, romantically, as though a good thing had died.

We think of the building of large and oppressive social structures as accomplishments, things to desire, and we mourn their passing as though the move away from that life is a loss.

But what if that loss is a gain?

Collapse As Gain

A book we’ll be taking a longer look at shortly is James C. Scott’s Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. I first mentioned it here.

One of his theses is that these large and oppressive structures — kingdoms and empires, giant cities and states — were not good, nor were they inevitable in the sense that they represented inescapable social advances. We don’t, in other words, “move forward” to life in large states, nor do we “turn into savages” when those states collapse. That’s a romantic notion, and an illusion.

Here’s Scott on the surprising (to most) four millennia span between the rise of sedentism (small village life) and the oppressions of “civilization” (life ruled by kings).

Note the “We thought … but it turns out” structure of the passage below. There are several of these pairs. From the Preface, all emphasis mine:

The astonishing advances in our understanding over the past decades have served to radically revise or totally reverse what we thought we knew about the first “civilizations” in the Mesopotamian alluvium and elsewhere. We thought (most of us anyway) that the domestication of plants and animals led directly to sedentism and fixed-field agriculture. It turns out that sedentism long preceded evidence of plant and animal domestication and that both sedentism and domestication were in place at least four millennia before anything like agricultural villages appeared. Sedentism and the first appearance of towns were typically seen to be the effect of irrigation and of states. It turns out that both are, instead, usually the product of wetland abundance. We thought that sedentism and cultivation led directly to state formation, yet states pop up only long after fixed-field agriculture appears. Agriculture, it was assumed, was a great step forward in human well-being, nutrition, and leisure. Something like the opposite was initially the case. The state and early civilizations were often seen as attractive magnets, drawing people in by virtue of their luxury, culture, and opportunities. In fact, the early states had to capture and hold much of their population by forms of bondage and were plagued by the epidemics of crowding. Finally, there is a strong case to be made that life outside the state—life as a “barbarian”—may often have been materially easier, freer, and healthier than life at least for nonelites inside civilization.

Each of those pairs deserves its own expansion — the surprising 4,000 year span between the first sedentary villages and plant and animal domestication; the place of wetland abundance, not irrigation, in pre-state sedentary lifestyles; the fact that fixed-field agriculture long preceded kingdom and state formation; and the fact that the agricultural life was not a step up in leisure, but exactly the opposite, a life lived as slaves to the land.

But for now look at the last point — The early states had to capture and hold much of their population by forms of bondage and were plagued by the epidemics of crowding.

There’s nothing romantic or desirable about living in crowds and filth (think Medieval cities and towns). I’ll add without citing for now David Graeber’s similar observation, that many hunter-gatherer tribes who tried fixed-field agriculture abandoned it later, just as the shepherds forced into British industrial hell-towns and factories would have loved to go back, if only their masters had not taken their fields away along with their freedom.

Escaping Civilization

This leads us to think about collapses differently. From Scott’s Chapter 1:

In unreflective use, “collapse” denotes the civilizational tragedy of a great early kingdom being brought low, along with its cultural achievements. We should pause before adopting this usage. Many kingdoms were, in fact, confederations of smaller settlements, and “collapse” might mean no more than that they have, once again, fragmented into their constituent parts, perhaps to reassemble later. In the case of reduced rainfall and crop yields, “collapse” might mean a fairly routine dispersal to deal with periodic climate variation. Even in the case of, say, flight or rebellion against taxes, corvée labor, or conscription, might we not celebrate—or at least not deplore—the destruction of an oppressive social order? Finally, in case it is the so-called barbarians who are at the gate, we should not forget that they often adopt the culture and language of the rulers whom they depose. Civilizations should never be confused with the states that they typically outlast, nor should we unreflectively prefer larger units of political order to smaller units.

Collapse as re-fragmentation. Not death, but rebirth, reconfiguration. The United States un-united, regionally governed. China the same. De-growth and de-globalization. Local control. More choices.

I’ll stop for now, but please consider that thought. Collapses aren’t always terrible tragedies, with fires and armies and death. They’re often just places abandoned because no one wanted to stay. The city collapses, yes, but its people now thrive, living separately, simply and well. No big screen TVs perhaps, but supportive communities replace heartless billionaire kings intent on their own aggrandizement at others’ expense. Fair trade? You’d get to choose.

Of course people will die, especially if the inevitable climate rears its head, but those consequences are, frankly, already baked in. We'll have them whatever we do. What will come out of that may be a blessing, not “collapse” in the tragic sense, but a wipe of the slate, a chance to construct a much more humane life.

If orderly restructuring fails (it’s failed so far), is “collapse” as considered above worse than violent revolt? I think I might choose the former, however hard, over the kind of great civil war we would otherwise get.

We line up to worship so many false idols these days. Greed, glitz and glamour are sought after more frequently than the goodness of God. So many are consumed with keeping up with Kardashians or any of the countless other social influencers, that sow discontent with our own lot in life.

Politicians, although tasked with representing the people, are for the most part dismal failures. Corruption and self interest too often take precedent, resulting in betrayal of the common good. No political party is innocent of this abandonment of principle. The current regime can't even be bothered to disguise the rot in its ranks. They are openly partnered with groups like Nazi racists, Christian charlatans and Technocrat antichrists. They all share the same rhetoric. A script of hatred for anyone that differs from their doctrine. Eventually, the glaring differences in the beliefs of this murky coalition against common decency will be their downfall. They will tear each other apart, fighting over the remaining scraps of civilization.

Will we people of compassion, kindness and love allow them to write the final chapter?

Thomas Neuburger, you go where others fear to tread: A very good piece, thanks.