Energy Rationing, Conscription and the Coming Climate Crisis

Let's take a trip to Fantasyland, to a world in which the U.S. addresses climate change in a meaningful way.

Let's take a trip to Fantasyland, to a world in which the U.S. addresses climate change in a meaningful way.

What does a meaningful response to climate change entail? Among other things, it means enacting the following two policies — energy rationing and conscription — and starting to enact them now. (Both are inevitable, of course, but probably not until after it matters, and not in an orderly way.)

Energy Rationing

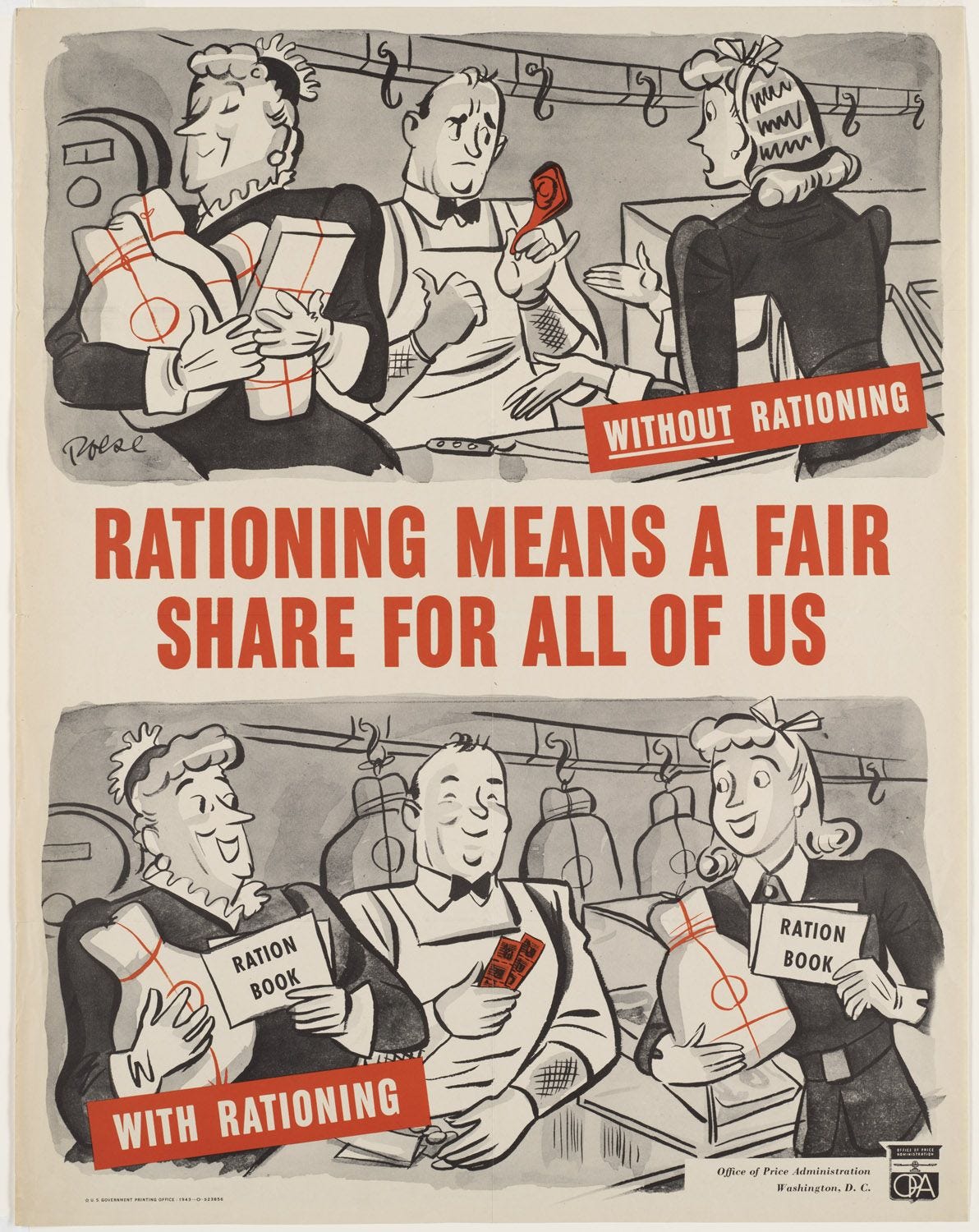

Let's look at rationing first, then turn to conscription of the population. To paraphrase something I wrote in 2019 ("The Elephant In the Room: Addressing Climate Change Means Rationing), it's very simple. We've dithered so long in addressing climate change that to address it effectively means not just a radical restructuring of the entire economy, it also means energy rationing.

The IPCC Special Report, "Global Warming of 1.5º C," calls for global carbon emissions to, in effect, "fall off a cliff" — to end, or at least start to end, almost immediately. This, of course, means ending the fossil fuel industry completely and forever.

Let's say we actually tried to do this — let's say that in 2021 [yes, I wrote this in 2019] a radical, FDR-style president and an awakened, panicked public committed to a crash conversion to 100% renewable energy. What would that mean for the consumer economy? Would that big screen, smart phone lifestyle, the one the energy industry says is at risk, actually be at risk?

This is where the answer gets obvious — of course it will be at risk.

If protecting people's ability to spend endlessly on consumer products is society's highest priority, then a crash-course energy conversion will be slowed however much it must be slowed to protect consumers first.

But if averting the global climate crisis is the highest priority, of course the consumer economy will take a back seat, to whatever extent it must.

This is exactly what occurred during World War II. This is what a "World War II-style mobilization" means.

In a perfect world, we'd start that energy restructuring now and we'd divert energy from the consumer economy — as we did in World War II — to do it. To quote Stan Cox on this:

We know from wartime experience that with resources diverted away from the consumer economy, shrinking supply will collide with still-high demand, bringing the threat of runaway inflation. Price controls will be essential, but with goods in short supply at reasonable prices, we will have to move quickly to prevent severe shortages, hoarding, and “rationing by queueing.” As in the 1940s, that will require fair-shares rationing.

Of course, given the mentality of our current crop of leaders — those who promise, for example, one-time Covid relief checks of $2000 before they win office, then renege the minute they achieve it — energy rationing won't occur before the crisis as a way to preserve the economy for the rest of us. Instead, rationing will occur after the crisis to make sure the economy of the wealthy and their attendant professionals, and only theirs, is protected.

Just as with Covid relief, the rich will be first in line, and likely the only ones served:

What would become known as the CARES Act became law on March 27, and the investor class has never looked back. While Americans struggle to file unemployment claims and extract stimulus checks from their banks, while small businesses face extinction amid a meager and under-baked federal grant program, the Fed has, at least temporarily, propped up every equity and credit market in America.…

The mere announcement of future spending heartened investors, who have relied on Fed support since the last financial crisis. This explains the shocking dissonance between collapsing economic conditions and the relative comfort on Wall Street. Between March 23 and April 30, the Dow Jones Industrial Average rocketed nearly 6,000 points, a jump of nearly 31 percent, creating over $7 trillion in capital wealth. The April gains were the biggest in one month since 1987.

The same month, 20.5 million Americans lost their jobs.

Yes, the men and women who rule us are that psychopathic. And yes, we continue to let them have their way. But in a better world — one we could have today if we gave ourselves better leaders — that's how it would be done. Energy rationing would start now so the whole economy could be rebuilt in an orderly way and with the least disruption possible.

Conscription

Conscription means marshaling the work of our citizenry to perform all the tasks needed to get through this crisis. Conscription can be into the military (as envisioned below) or into a civilian work force like the New Deal era CCC.

Either way, quite a lot of labor will be needed to restructure and repair this country. How much? Consider this piece by Col. Lawrence Wilkerson (emphasis added):

The All-Volunteer Force Forum was founded in 2016 to begin stirring up a debate across the United States on how the country populates its military. Since then, it’s been an uphill battle, but hosting conferences at universities across the country — and coming up in March, at the Catholic University in Washington, DC — has at least put the forum and the debate on the national map. Working with the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service also helped give the forum some heft.

It was inevitable that the climate crisis — arguably the most catastrophic crisis the United States, indeed, the world, is facing — arose as one of the several force-defining threats the forum has addressed that might require the country to resume conscription. Millions of young, healthy, dedicated, well- and specially-trained men and women will be required to manage both the domestic and the international threats created by this crisis.

Seems reasonable, even necessary. Wilkerson explains in detail:

In the domestic realm, fighting massive fires, meeting the emergency requirements following multiple hurricanes striking simultaneously or unexpected deep freezes like the one currently ongoing in Texas, dealing with disappearing shorelines and even whole swaths of developed land suddenly overwhelmed by the sea, dealing with massive flooding following torrential and constant rains, and managing the temporary camps and facilities set up to house millions of homeless people, are just a few of the new missions they will confront, undertake, and manage between now and the close of the century.

Internationally — while the U.S. reputation for taking the lead in disaster relief and humanitarian assistance has taken significant blows over the past four years — there is no doubt that possessing unprecedented power projection capabilities means that the U.S. military will need to be at the forefront of such operations.

In addition to the many crises caused by sea rise, the more intense typhoons in the Pacific, the flooding and then the drying up of water sources occasioned by Himalayan glaciers disappearing, the coming massive changes in the Arctic and the Antarctic regions, the desertification of land, the acidification of the oceans, the salinization of coastal water wells and other supplies, and the lack of viable agriculture, will so rack the world that the U.S. military will be run ragged attempting to keep up.

That's a hefty list, and as he points out, the current army, the All Volunteer Force, will be "utterly incapable of meeting these domestic and international challenges even if they were to occur separately, which they won’t."

Simply looking at the likely mission sets tells us several millions of troops, skilled in both traditional and completely new missions, will be necessary. Perhaps the Civilian Conservation Corps of the 1930s is a model, though the overall mission would not be preparation for war but preparation for the survival of much, if not all of the human race.

Thus, we need a new mission set — domestic disaster relief on an unprecedented scale, agricultural skills pertaining to new and very different forms of food development and distribution, and refugee management aimed at millions of displaced people and construction of the massive encampments to house them.

We’ll also need flood control and flood repairs that might include the construction of dams as well as their demolition, construction of water facilities and even desalinization plants that turn seawater into fresh, potable water.

We’ll need to open new lands further north to extend food-growing capacity and we’ll require management of remedial actions to be taken should the Arctic, the Antarctic, or even Greenland’s ice packs suddenly deteriorate rapidly and add meters to the levels of sea rise. And we’ll need life-saving aid to desperate peoples all over the globe.

To do this, Wilkerson suggests that planning start now, that the Selective Service (the draft) be reformed, that Congress re-initiate full conscription, and that the military be divided into two parts, a smaller war-fighting force similar to what we have today, and a new, far larger contingent focused on climate-related tasks.

Again, perfectly reasonable, even necessary.

After all, as the crisis hits, who's going to fight "massive fires," meet the requirements of "multiple hurricanes striking simultaneously," deal with "unexpected deep freezes" and "disappearing shorelines," relieve the damage of "massive flooding following torrential and constant rains" and manage the "temporary camps and facilities set up to house millions of homeless people"?

It will have to be the government, whether the effort is organized under the Pentagon or another agency. And to do that, the government will have to be prepared. Given the scale of mobilization needed, if those preparations don't start now, they'll never be ready in time.

Do you expect the Biden government — or any U.S. government not led by someone like Sanders — to even start to be ready? Neither do I.

Will there be mass mobilization after the crisis occurs? Of course. But given the demand on our resources relative to supply, to whom will those resources primarily go?

If past is prologue, the rich will be first in line, and likely the only ones served.

This is an updated version of a previously published piece.

Which will be worse - the effects of climate change (assuming it, of course, is true, which is a very big assumption) - or the effects of increased government tyranny resulting from attempts to address climate change (which is a certainty)?

As a scientist who knows the politics of science being funded by government, of the pitfalls of scientific modelling, and of the poor record of science to predict the future, I would prefer to take my chances and be self-sufficient. And I would guess others would choose as I do if they fully understand the situation. But alas, democracy more often than not equates to idiocracy.