Bad News for Oil, Good News for Water

As the price of oil heads up, the cost of water could be coming drastically down

Two items for this week, one ominous — it’s an ominous world these days — and one truly hopeful. Let’s start with the bad news and end with the good.

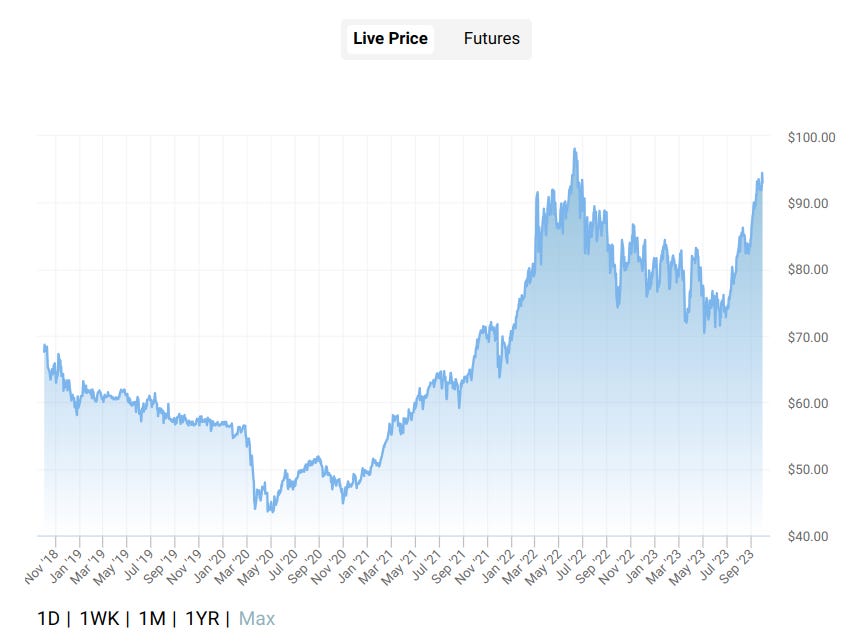

Is crude oil headed for $150 in 2026?

According to the analysts at JPMorgan, crude oil is headed from today’s price in the mid-nineties to as much as $150 a barrel. That would be clearly devastating for American households, not only for the resulting price of gasoline and heating oil, but also for the price of all energy-dependent goods, which is most of them.

From OilPrice.com:

JPMorgan’s head of EMEA energy equity research, Christyan Malek, warned markets on Friday that the recent Brent price surge could continue upwards to $150 per barrel by 2026, according to a new research report.

Several catalysts went into the $150 price warning, including capacity shocks, an energy supercycle—and of course, efforts to push the world further away from fossil fuels.

Most recently, crude oil prices have surged on the back of OPEC+ production cuts, mostly led by Saudi Arabia who almost singlehanded took 1 million bpd out of the market, followed by a fuel export ban from Russia. Increased crude demand paired up with the supply restrictions, boosting crude oil prices and contributing to rising consumer prices.

For this year:

JPMorgan said in February this year that Oil prices were unlikely to reach $100 per barrel this year unless there was some major geopolitical event that rattled markets, warning that OPEC+ could add in as much as 400,000 bpd to global supplies, with Russia’s oil exports potentially recovering by the middle of this year. At the time, JPMorgan was estimating 770,000 bpd in demand growth from China—less than what the IEA and OPEC were estimating.

But:

JPMorgan now sees the global supply and demand imbalance at 1.1 million bpd in 2025, but growing to a 7.1 million bpd deficit in 2030 as robust demand continues to butt up against limited supply.

JPMorgan blames the supply imbalance on “capacity shocks, an energy supercycle,” and of course, efforts to deal with climate change. The word “Ukraine” never appears, but the Russian export ban gets a mention.

Is this likely? I’m not sure, but there are forces in the world that can’t be forced, and keeping us stuck on oil is one of them. To the extent that oil is cheap enough to power this overburdened planet for decades ahead, that’s the size of the flood of trouble we’ll face when the big dams finally break.

Do we want to face a fraction of that trouble now, in exchange for better times to come? Our betters, in their usual self-dealing way, are not giving us that choice.

Desalination system could produce freshwater that’s cheaper than tap water

You read it right. That’s the news from MIT, and it’s refreshing indeed.

MIT engineers have been working on a passive system to use the sun’s energy to evaporate and capture fresh water from salt water sources, and after three iterations, they appear to have gotten it right.

MIT engineers and collaborators developed a solar-powered device that avoids salt-clogging issues of other designs.

Engineers at MIT and in China are aiming to turn seawater into drinking water with a completely passive device that is inspired by the ocean, and powered by the sun.

In a paper appearing today in the journal Joule, the team outlines the design for a new solar desalination system that takes in saltwater and heats it with natural sunlight.

The configuration of the device allows water to circulate in swirling eddies, in a manner similar to the much larger “thermohaline” circulation of the ocean. This circulation, combined with the sun’s heat, drives water to evaporate, leaving salt behind. The resulting water vapor can then be condensed and collected as pure, drinkable water. In the meantime, the leftover salt continues to circulate through and out of the device, rather than accumulating and clogging the system.

The new system has a higher water-production rate and a higher salt-rejection rate than all other passive solar desalination concepts currently being tested.

I’m especially pleased to see that it’s a passive device — no moving parts, no required energy input (read, fossil fuel) other than what we freely get from the sun.

[T]he researchers calculated that if each stage were scaled up to a square meter, it would produce up to 5 liters of drinking water per hour, and that the system could desalinate water without accumulating salt for several years. Given this extended lifetime, and the fact that the system is entirely passive, requiring no electricity to run, the team estimates that the overall cost of running the system would be cheaper than what it costs to produce tap water in the United States.

Human water needs are roughly three to four liters per day. A one-square-meter device producing five liters per hour could supply up to twenty-five people for years without needing maintenance. That’s very good news.

My only concern: The design, when it’s all worked out, should belong to the public, not Wall Street ghouls who think water’s their ticket to wealth.